What is the tao? (Part 1)

The Lao-tzu, a.k.a. the Tao te ching — see especially the Penguin edition with introduction by D.C. Lau — presents us with a philosophy that seems elusive, even alien. Its central concept is the tao, the "way." What is the way or the tao (pronounced "DOW")? |

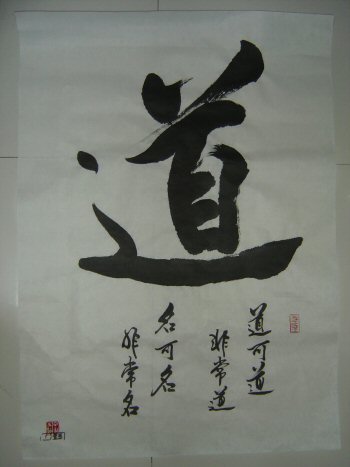

| Tao and the first line of Tao te ching |

The way that can be spoken of is not the constant way (ch. 1, first line).

Accordingly, the way is called "forever nameless" (ch. 32). This "nameless" way defies all language, all attempts to pin it down in words. The way transcends thought and language.

Also, we read mysteriously in ch. 42:

The way begets one; one begets two; two begets three; three begets the myriad creatures.

Here, the "myriad creatures" are all the concrete things in the universe, animate or inanimate, with all their manifold types and categories. All owe their existence to a succession of numbers, and thereby to the tao: one (as the tao), then one (as the metaphysical One, or Unity), then two, then three (and so on).

We are reminded of the mathematicians' Fibonacci sequence: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13 ... . In this sequence, from which can be derived all sorts of geometric relationships that permeate observable nature, add any adjacent pair to get the next in the sequence. Add 0 (representing primordial nothingness) and 1 (representing the tao) to get 1 (representing the metaphysical One). Then add the first occurrence of 1 to the second occurrence of 1 to get 2, standing for the pair of opposites, yin and yang. And so on.

In this numerological way, the tao, as the first of the two 1's in the Fibonacci sequence, "is conceived of as that which is responsible for the creation as well as the support of the universe" (Lau, Introduction, p. xv).

This relationship of the tao to the Fibonacci sequence may (I humbly suggest) help overcome a confusion to which Lau himself seems to fall prey: that between the tao and "the One."

In a way, the tao can be thought of as conceptually pre-existing the One. If we think of the monotheistic God of Western religion as personifying the metaphysical One, the tao is something else — something upon which even God is based. (We read of the tao in ch. 4, "It images the forefather of God.")

Investigating the tao is not to deny God; it is to investigate an impersonal principle from which even our concept of God proceeds. For the tao is emphatically not a person. Instead, the tao transcends the person-nonperson distinction ... as it transcends all pairs of opposites.

Here we get another clue as to why the tao, when we contemplate it, seems so elusive and alien to our thought. The tao, Lau points out, "is responsible for the strong being strong [and] it is no less responsible for the weak being weak" (p. xvii). It accordingly cannot be identified with either partner in any pair of opposites (except of course as a rhetorical ploy, when so doing helps us understand it better):

Thus we can see that no term can be applied to the tao because all terms are specific, and the specific, if applied to the tao, will impose a limitation on the range of its function. And the tao that is limited in its function can no longer serve as the tao that sustains the manifold universe (p. xviii).

But, Lau shows, such talk flies in the face of our most basic assumptions in the West, inherited from Plato.

Plato vested all reality in a plurality of ideal Forms such as the Form of Roundness which, unlike all round things, uniquely is perfectly round. No material ring or orb is as perfect in its roundness. "Plato's insistence," says Lau (p. xviii), is "that of anything real we must be able to make a statement to the exclusion of its contradictory." Accordingly, we must be able to say of any truly real round thing that it is in no way, shape, or form not round. We must be able to adopt one of some pair of opposites (say, round) and wholly exclude the other (not round). Only then is something truly real.

The Taoist who reads the Lao-tzu would be mystified at this, which (per Lau, pp. xviii-xix) amounts to assuming that "the totally real must be totally knowable." That which is truly round (or truly square or truly hot or truly cold, etc.) has the advantage of being fully knowable ... even if it's only an immaterial Form or Idea, and can never be an actual object.

But the tao is just the opposite: unknowable. Or, at least, it's not totally knowable. The Taoist is "quite prepared to accept" the consequent notion that "the truth must also be ineffable."

So Plato, whose thought permeates all thought in the West, went in search of a rationale for avoiding the possiblity that "the real" may not be fully knowable, and that "the truth" may not be within our power to define.

We Westerners are, by reflex, Plato's heirs. We want, we insist, that we can take control of worldly affairs, however imperfect and "unreal," by asserting their relationship to some superior, though fully knowable, Form or Idea which alone is real and true.

It is our "can-do" philosophy which we inherit from this ancient Greek thinker. By taking reality out of the realm of the physical world and investing it in a higher order of Forms, Plato gave us the wherewithal to master the physical realm. We in the West have been doing so ever since.

Put another way, we in the West have been what the Lao-tzu calls "clever." That is, we have invested heavily in increasing our own "knowledge." In so doing, we have intensively fed our own "desire."

"Desire" is used in the Lao-tzu as a synonym for ambition, for covetousness, for ever wanting more-more-more ... for not being "content." This unbridled restlessness, Lau points out, depends on "knowledge." "It is through the knowledge of what is desirable that desire is excited," he writes (p. xxxi). "It is for this reason that," in the philosophy of the Lao-tzu, "knowledge and the clever come in for constant stricture."

And so we have a double reason why the Lao-tzu speaks of the tao in primarily negative terms. One is that the use of verbal negation — e.g., "The way that can be spoken of is not the constant way" — avoids the trap of positive statements' tendency to limit inappropriately the illimitable range of the tao's function.

And the second reason is that verbal negation is necessary to counter the Platonist lurking in all of us, especially if we are from the West. Through negation is offset our lust for knowledge — our rambunctious cleverness — and the discontent it inevitably sows. Then and only then are we open to the way, the neverending tao.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home