The practice called

qigong is a close cousin to Tai Chi. It's pronounced "CHI GUNG" and can be spelled that way. It's discussed at some length in the book pictured at right,

T'ai Chi for Dummies

.

The

qi or Chi spoken of in the name of this meditation method refers to the energy which flows in your body. It needs to flow freely along certain pathways or meridians, but when the body grows tense, the muscles and joints clench up, or the posture is wrong, the meridians become kinked, like hoses. Energy doesn't flow right, with all kinds of negative results.

Qigong fixes that. Through it, you learn to right your posture, relax your muscles, and "root" your body firmly to the earth, such that the earth's energy can flow into you and add to your Chi.

Qigong is done with only very gentle movements, or none at all. The exercises are meant to (among other things) get your "microcosmic orbit" going properly. That's a loop of energy flow that runs up the front of your body from the

dan tien point ("DON TYEN," "elixir field") between your belly button and pubic bone. It ascends all the way to the

bai hui ("BY HWAY," "hundred meetings") point atop your head. Then it heads down the back side of you, passing through the

ming men ("MING MUN," "gate of life") point between your kidneys. From there, it curves down through your pubic area and up again to rejoin the

dan tien.

One of the perhaps surprising things about all this is that the

dan tien is thought of as a storehouse of

sexual energy. This sexual energy needs to flow all around the "microcosmic orbit."

One of the basic

qigong exercises is "Standing Like a Tree."

The Chinese for it is

zhang zhuang, "JAN JWANG." It involves no movement at all. Although Therese Iknoian, author of

T'ai Chi for Dummies, describes five different variations of Standing Like a Tree, different in terms of how you hold your hands and arms, the posture shown at left is typical. It is the posture known as Embracing the Tree or Embracing the Heavens. The illustration comes from

this web page, a part of

CHI Online, the website of the Center for Holistic Instruction. Check out their page devoted to Tai Chi itself

here.

Another variation of Standing Like a Tree has you simply hang your hands at your side, keeping everything else the same as in Embracing the Tree ... in which case you are basically in the Wu Chi or "Infinite Ultimate" position I talked about

here and

here.

You simply stand in one of these positions for anywhere from 2-3 minutes, early on, to 20-30 minutes as you gain proficiency. You take care to get your posture just right, according to instructions Ms. Iknoian gives (pp. 76-78), because any defects of posture will kink up your Chi hose. As you stand there, the idea is that you can't help but enter a meditative state ... as, also, your Chi commences to flow optimally. (Of course, it may take days, weeks, or months of practicing before you achieve this result.)

In my earlier posts, I suggested that entering the Wu Chi posture seemed to do me good almost instantly. It really woke me up, making me come noticeably alive, while at the same time making me feel relaxed and mindful.

It even relieved me of the pressing urge to use the toilet, a relief which lasted several hours.

I personally can really relate to a meditation method which does not require doing anything mentally arcane, but just cultivates the body's own natural ability to bring the mind along with it! I'll be trying some of the

qigong exercises and reporting back.

It has come to my attention that Wu Chi is considered a form of meditation all by itself. Web pages about the meditation and the philosophy behind it include:

Apparently, Wu Chi is the primordial nothingness, void, or emptiness. Wu Chi accordingly proceeds from the tao, and with it the constant interaction of yin and yang — which is what Tai Chi basically is — necessarily begins.

|

Circle as symbol

of wuji |

|

Tai Chi symbol:

yin and yang |

No wonder we assume the Wu Chi position, or a variation thereof, at the beginning of any Tai Chi form. No wonder my individual Tai Chi exercises, as prescribed by Master Lam in

Step-by-Step Tai Chi, now begin with a two or three minutes of this "Standing Meditation" posture.

Incidentally, I can add a degree of confirmation to my

earlier post on Wu Chi, in which I mentioned that adopting this posture (which is pretty much maintained during the subsequent "Strength and Motion" exercises)

does in fact seem to relieve the urgent need to empty the bladder. I felt, and resisted, the need before beginning my exercises today. I tried starting with the "Fundamental Movements" exercises, which do not involve the Wu Chi position. It was no go. I felt like I had to run to the bathroom. But instead I went into Wu Chi, and almost immediately my urge vanished. After two or three minutes, I continued by going back and doing "Fundamental Movements." Then I did the Wu Chi-oriented "Strength and Motion" exercises. The entire session lasted an hour.

When I was done, I sat at the computer and did some work for this blog, looking up "Wu Chi" on Google, composing this post, etc. It's now 2-1/2 hours since I used Wu Chi to quell my strong bladder urge, and, no, I haven't gone to the bathroom. Though I naturally feel like I could go now, or soon, there's no sense of urgency.

I'm going to keep experimenting with Wu Chi posture as a bladder-control technique. It seems to me it could come in handy when I'm stuck in a line waiting for a urinal, as occasionally happens when there's quite a crowd.

And I'm wondering if "Wu Chi bladder control" couldn't help women even more, given that the lines just to get into the rest room can be even longer, in their case, than men's in-restroom queues for a urinal.

I am using

the book

Step-by-Step Tai Chi, by Master Lam Kam Chuen, to help me learn to practice Tai Chi. It's divided into various sections of exercises, from easier to more difficult. I'm dipping into the second section, exercises for "Strength and Motion," now. I plan to continue doing the first exercises, "Fundamental Movements," on certain days as well.

The first "Strength and Motion" exercise is, quite simply, "Standing in the Wu Chi Position," done for two to three minutes. Most of the subsequent exercises in the section also begin by having you adopt this so-called "position of primal energy." As described by Master Lam, Wu Chi involves standing with your feet shoulder-width apart, pointing directly forward and not at an angle. With your shoulders relaxed and your hands loose at your sides, you point your face and gaze straight ahead, imagining "that your head is lightly suspended from a fine thread."

That's Part One of entering Wu Chi posture. Part Two is to slowly bend your knees such that your head is lowered about two inches. This amounts to bending your knees just enough that their fronts come roughly even with the line where your toes join your feet ... but no further. You can check this alignment from time to time by glancing down, but don't lean forward to do it. That gives you a false reading and encourages you to bend your knees too much. In fact, instead of thinking of bending the knees, you'd be better off thinking of "softening" them just a tad.

You should spend most of the Wu Chi time with your head up. Your upper body needs to stay relaxed, and your weight needs to stay "evenly distributed over both feet" and "centered in the middle of the soles of your feet."

(I cheat a bit and do this while standing sideways to a full-length mirror, with minimal clothing on. That way I can quickly check my knees-toes alignment by glancing down and my upper-body posture by glancing sideways, before returning my head to its forward-looking position.)

As you serenely maintain this posture, your breathing should remain "calm and natural." After two or three minutes, you simply come up out of the gentle crouch, stand "relaxed and still for several seconds," then move on to the next exercise ... which, of course, has you resume the Wu Chi posture before adding other movements.

A similar set of instructions for the "Standing Meditation for Taiji" posture may be found

here, at the

Touch of Tao website. It is by by Cynthia McMullen. "Standing Meditation" is an alternate name for Wu Chi.

Now, here's the thing. This morning I woke up feeling less-than-refreshed from my night's sleep ... so much so that I considered not practicing Tai Chi today. But I decided to do so anyway, and when I adopted the Wu Chi position, after just a minute or so I began to feel great! My body and mind felt quickly revivified, and I began to marvel at the notion that this posture has been aptly chosen indeed as the activator of "primal energy." How odd that simply standing in a particular, seemingly odd posture can have such a profound effect on the body-mind unit.

I hasten to note that you have to work up to staying in Wu Chi Standing posture for long periods of time, because it is frankly hard on the leg muscles if you're not used to it.

Also, I have found that subtle changes in upper-body posture make big differences. Today, as I was standing in Wu Chi it came into my head that I ought not to tuck my pelvis forward quite so much, but put just a little more arch in my lower back ... and doing that immediately felt "right" to me. (This is my personal experience. I note that Ms. McMullen advises "the pelvis is tucked slightly forward so the lower spine is straight." I imagine I ordinarily carry my pelvis tucked

too far forward, and so I have to consciously "untuck" it a bit to get Wu Chi right.)

Update: After further experimentation, I seem to be finding that Ms. McMullen's advice about tucking the pelvis slightly forward is correct for me, after all. I also find that I was initially bending too much at the knees — because I was leaning forward slightly to check the knees-to-toes alignment, and because I was thinking the knees ought to line up with the "fronts" of the toes, not the "backs." With the knees bent that much, I was bringing on stiffness and soreness in my knees as a result of doing the exercises. And the extra bend at the knees brought my pelvis too far forward, which is why I had to consciously "untuck" it somewhat. So I was also getting stiffness and soreness at the bottom of my back.

The lesson here is to remember to do these postures and exercises gently and correctly and to make sure you're not hurting yourself! If it doesn't feel good, stop, figure out what's wrong, and correct it. (End of update.)It works as advertised! In other words, there really do seem to be pathways or meridians along which

qi, or Chi energy, flows through the body, and if you adopt just the right posture, they open up nicely!

(Another good thing: I

posted earlier some questions I have about "Tai Chi and bladder control." I said that I sort of hope Tai Chi can help me with my irritating, everyday gotta-go-gotta-go urges. So at the start of this morning's session, though I had the urge to go, I decided to wait and see if the exercises had any effect on that situation. And they did! The urge to relieve my bladder vanished and I was able to go another two or three hours without visiting the bathroom.)

The lesson here is that Tai Chi is not just another form of exercise. There's something special about the exercises and postures that are chosen ... a fact which your body quickly proves to you, even if you are a rank beginner.

I suppose I've been avoiding the question the relationship between Tai Chi and one's sex life. This isn't because the question hasn't popped into my head. Rather, none of the Tai Chi authorities I've encountered so far have said much about sex (unless you count groups of men pulling flatbed trailers with their penises; see

this earlier post).

So I googled "Tai Chi" and narrowed the "about 4,160,000" results I got by adding "sex." That gave me "about 234,000" results.

I should hastily note that I do not presently have a wife/girlfriend/significant other, and so what I found is somewhat theoretical, from my standpoint.

One of the first results listed by Google (click

here) was:

www.IntimacyRetreats.com presents Tantra Tai Chi

Transform your relationship into a Love Affair!where I read:

The purpose of the program is to bring your mind's attention to your body's presence. When you become mentally and physically centered in your body, you become more open to your naturally joyous state of being. You enter into the "here and now," where only Love is present. Past and future disappear, only the eternal moment exists.

This program seems to combine Tantra or Tantric Yoga from India with Tai Chi from China. I'd like to know whether Tai Chi alone can make for better sex.

A

Tai Chi Newsletter at

this site offers this:

Tai chi offers an increased awareness of this chi. So does sex. The pre-orgasmic state of vibration, of profound energy flow is a classic example of chi movement. Interestingly - the cultivation (and increased awareness) of tai chi energy can help with the cultivation of sexual energy and vice versa. (Note sexual chi is often cultivated through various Tantra practices).

Mmm-hmmm. Encouraging. But Tantra seems to be creeping in again. Again, what happens if I just want Tai Chi ... and, of course, great sex?

"According to 'Self' magazine," a snippet to be found here says, "women who practice tai chi have more sex than women who do any other type of exercise. In fact, 39 percent have sex at least five times a week." Dunno what to make of that!

There seem to be a fair number of websites that credit qigong (say, "CHEE GUNG") with boosting one's sex life. Qigong is a close cousin of Tai Chi, about which I have yet to find out much about. A webpage of the Tai Chi For Health Institute here describes one of its courses, "Qigong and Oriental Healing Arts":

Maintaining health through the integration of body, mind and spirit is the focus of this workshop. Students learn the basics of Qigong, beginning with stress release, detoxification and energy gathering exercises. Basic breathing techniques are introduced as well as recommended methods of sleeping, eating, standing, walking and "dual cultivation" (sex).

I plan to come back to this subject, accordingly, when I figure out more about what

qigong is, and how it relates to Tai Chi.

This is Part 4 of my inquiry into the nature of the "way" or

tao. (See Part 3

here.) My topic this time: the essentialness of "knowing when to stop."

Chapter 44 of the

Tao te ching or

Lao-tzu reads, in part:

Know contentment

And you will suffer no disgrace;

Know when to stop

And you will meet with no danger.

You can then endure.

(See the full chapter text and commentary here.)

According to D.C Lau in the introduction to his Penguin Classics translation of the Lao-tzu, shown at right:

in the introduction to his Penguin Classics translation of the Lao-tzu, shown at right:

The precept in the Lao-tzu is that we should hold fast to the submissive. (p. xxiii)

By this he means that Taoism values the submissive (Chinese

jou or

rou) above just about everything. Close synonyms for "submissive" are "weak" and "bent." The submissive, the weak, and the bent, as qualities of the neverending

tao, eventually overcome the stubborn, the strong, and the straight.

Hence he or she who wants to live out his days and not have them unnecessarily shortened will be "submissive," "weak," and "bent," like the

tao itself. For the

Lao-tzu, says Lau, is first and foremost a manual for keeping on keeping on. To make this crucial point he notes, "It was to the solution of this problem of survival [in the turbulent Warring States period] that much of the wisdom of the

Lao-tzu was directed" (p. xxvii). Lau adds, "The supreme goal for the common man as well as for the ruler is survival, and the means to this goal is simply to hold fast to the submissive" (p. xxxvi).

Keeping this fact in mind may help to offset much of the abstract, high-flown philosophizing I engaged in in previous installments of this series. As the back cover of Lau's Penguin Classics edition states, "As a treatise both on personal conduct and on government [the

Lao-tzu] is moral rather than mystical in tone, and advances a philosophy of meekness as the surest path to survival."

To that I would add that "personal conduct," in the

Lao-tzu,

is a form of "government" — government of the

self — so that they are in fact one and the same topic. I would also add that "ethical" might be a better word to use than "moral," which carries overtones of scrupulosity and censure which are absent from the

Lao-tzu. The

Lao-tzu is as a result an intensely

practical — albeit elusive — guide to "right" conduct, where the latter is defined as that which allows us to endure in a universe which proceeds from, by, and according to the

tao.

It is in this context that "knowing contentment" and "knowing when to stop" become more than mere mottoes and facile shibboleths. They are the

sine qua non of survival.

Another word for the quality the

Lao-tzu extols as submissiveness is "suppleness." This is what the

Lao-tzu means by saying

One who possesses virtue in abundance is comparable to a new born babe. (ch. 55)

or

If you are a ravine to the empire,

Then the constant virtue will not desert you

And you will again return to being a babe. (ch. 28)

|

jou or rou

"supple, pliant,

submissive" |

For it is the infant's suppleness which the

Lao-tzu has in mind here. The word

jou, Lau points out (p. xi), means "supple, pliant, submissive."

A baby is supple, even rubbery, and can survive rough handling. A dead person is just the opposite: rigid. In between comes the brittle state of the old.

Moral: if you want to live long, move in the direction of cultivating the suppleness of a newborn babe.

I'm taking a day off from Tai Chi. I've been pushing rather hard recently to increase my proficiency at the various exercises I've been doing — with a fair amount of success, I must say, especially with regard to my balance and body control when Tai Chi Walking! But my knees and various other of my joints and body parts have gotten a bit stiff and sore. I think a day off is indicated.

Meanwhile, I am interested in learning more about how Chinese is written, and particularly the art of Chinese calligraphy.

There appear to be several books available on the subject. At left is Johan A. Bjorksten's

Learn to Write Chinese Characters. (Click on the image to "Look Inside" the book at

Amazon.com.)

Bjorksten says the beautiful characters of Chinese writing are of four types. One type is the

pictograph. An example is the character for the word

men, which means "door," and which is pronounced "MUN."

|

men

"door" |

This character actually looks something like the paired doors which are familiar as the entrance to a saloon in the American West. Bjorksten shows the ancient version of the modern character, and it looks even more like swinging saloon doors. That's why it's a pictograph: it looks like what the word means.

By the way, I'm borrowing the images of Chinese characters which I show herein from the Chinese Character Dictionary at

www.chinalanguage.com. You can click on the images to get more information. Except in their basic form, they don't look much like the flowing characters in Bjorksten's book. They are referred in the Character Dictionary to as "glyphs." I assume that, as represented online, they are no more calligraphic than any letter of the English alphabet printed in an ordinary book.

Bjorksten's second character type includes

characters depicting abstract concepts. One of these

|

shang

"above" |

is

shang, "above" (pronounced "SHAHNG"). Although it is not literally a pictograph, or stylized picture of some object, it does manage to convey the idea of "over" or "above," no?

Then there's the abstract concept, "good." In Chinese, it's

hao (pron. "HOW").

|

hao

"good" |

Bjorksten says it comes from a picture of a woman holding a child! In the ancient version, the woman is quite obviously the figure on the left, the child on the right. The crossmember on the "modern child" is an abstraction of the "ancient child's" outspread arms.

The third type of character is the

phonetic-radical combination. An existing character is used over again — "borrowed" — but its meaning is changed. The pronunciation of the new character — the "phonetic" — is usually that of, or at least hinted at by, the pronunciation of the borrowed character. But the addition of a "radical" to the way the borrowed character is written marks it as having a different meaning.

For example, take

cao (pron. "TSOW").

|

cao

"grass" |

Bjorksten says it is made up of a phonetic,

zao ("ZOW" or "DZOW"), which by itself means "early" — a fact which is irrelevant here — and a radical sitting atop it whose general meaning is "plant." In the case of

cao, that general meaning becomes the more specific one of "grass."

|

zao

"early" |

To the right, I show the Chinese Character Dictionary rendering of

zao. It is easy to see that there is no "extra" element in the

zao character, as there is in

cao. Accordingly, the radical in

cao is the "hat" that has been placed on top of

zao. It looks to us Westerners like goalposts with the crossbar extended out on each side.

So the concept is clear: the pronunciation comes, with minor changes, from one part of the character, the phonetic; the meaning, from the other part, the radical. In this case, the pronounciation is the same for

zao and

cao except that the leading consonant changes from "Z" or "DZ" to "TS."

Bjorksten goes on to give us English speakers a way to visualize this phonetic-radical hybridization process. Suppose in English it were necessary to represent the verb "to read" as a phonetic plus a radical. For the phonetic we would very likely choose a word such as "reed" — a word whose meaning has nothing to do with reading.

Rather, "reed" is a

homophone of "read," giving the intended pronunciation. But the

meaning of the word we are cobbling together will come from, Bjorksten says, a separate radical that is added to the phonetic. The radical we'd choose might be "eye," since the eye is used for reading. The "eye" radical would indicate

which homophone in the "read"/"reed" group is intended.

So our cobbled-together word would be pronounced "reed," but, as written out, it would look more like "eye-reed." Clumsy, admittedly, in a language which like English is written with an alphabet. But in a language like Chinese which is written with stylized pictures or glyphs, elegant indeed! Bjorksten says that over 95% of Chinese characters have been formed in this elegant phonetic-radical hybrid fashion.

In the history of spoken/written Chinese language, which goes back 6,000 years, there has quite obviously been a sloshing back and forth between sound and meaning. This fact accounts for Bjorksten's fourth major type of glyphs:

characters borrowed without adding a radical.

An example is

lai ("LIE"), originally meaning a kind of wheat, but now meaning "to come."

|

lai

"to come" |

This character was borrowed from its original meaning to represent the verb "to come." I assume that, in spoken Chinese, the word for this particular kind of wheat and the word for "to come" are homophones — they have the same sound, the "LIE" sound of

lai. But in this particular case, for whatever reason, the meaning of the original phonetic was

not overridden or modified by the addition of a radical. Chinese readers just know to ignore the "kind of wheat" meaning in favor of that of "to come."

And so we see that written Chinese is a language of great complexity, compactness, and elegance — a perfect candidate for the calligrapher's art!

I wrote in

"What is the tao? (Part 2)" of the Taoist attitude of present-tense-hopefulness-in the here and now — in contrast to the future-tense-hoping-

for an idealized hereafter which is the habit of us Westerners, since we tend to be heirs of Platonic thought that has been filtered through our principal religions. The Taoist insight, I said then, is that things in our world are not fundamentally "broken" and do not need to be "fixed."

Does that mean absolutely nothing is ever wrong in this world? Not by a long shot.

Does it mean that we should always run around with beatific smiles on our faces? Only if we have cultivated the right mindset, in which case smiles are superfluous. One who is truly tranquil smiles only when the occasion calls for it.

Does it mean we don't need to change a thing? Just the opposite. The Taoist assumption is that we tend to have a wrong mindset, from which proceeds all those unfortunate things in our world which could have been avoided. We need to cultivate the right mindset again. Though, paradoxically, it is the most

natural way of being in the world, we have lost the trick of it. Taoist theory and practice is a way of reclaiming the trick.

In order to convey to us the nature of the right mindset, the

Lao-tzu speaks of the "uncarved block." Chapter 37 (see

this page at the

CenterTao website) reads:

The way never acts yet nothing is left undone.

Should lords and princes be able to hold fast to it,

The myriad creatures will be transformed of their own accord.

After they are transformed, should desire raise its head,

I shall press it down with the weight of the nameless uncarved block.

The nameless uncarved block

Is but freedom from desire,

And if I cease to desire and remain still,

The empire will be at peace of its own accord.

So the thing which we most need is to get back to being a "nameless uncarved block," like the true Taoist sage who alone is eligible to be "lord" over the "myriad creatures."

But what does that mean?

According to D.C Lau in the introduction to his Penguin Classics translation of the Lao-tzu, shown at right:

in the introduction to his Penguin Classics translation of the Lao-tzu, shown at right:

[T]he uncarved block is in a state as yet untouched by the artificial interference of human ingenuity and so is a symbol for the original state of man before desire is produced in him by artificial means. (p. xxxii)

We see that, in a sense, the "nameless uncarved block" represents a natural, even Edenic, state, prior to the onset of "artificial" desires. But why must the natural "uncarved block" be called "nameless"? Lau continues:

The nameless uncarved block is nameless because it has not shattered and become vessels. (p. xxxiii)

Chapter 28 of the Lao-tzu says:

When the uncarved block shatters it becomes vessels.

The sage makes use of these and becomes the lord over the officials.

Here, the relationship of "vessels" to the "uncarved block" is the same as the relationship of all the minor officials/specialized functionaries/department heads to the ruler. The department heads or "vessels" have names indicating their specific functions. So only its very namelessness saves the uncarved block from the differentiation and consequent appropriateness of giving names that goes along with diverse specialization and competing "departmental" interests. This "namelessness" of the ruler, because it does not limit or pigeonhole him, is what qualifies him alone to be "lord over the officials."

One way to look at it is this: the "namelessness" of the ruler signifies his essential centeredness. Any "name" — any specific function or special interest, such as that of a "vessel" or department head — pulls the "govenrnment" this way or that, and therefore off-center.

Of course, we are free to take all this talk of rulers, vessels, government, and so forth as a metaphor for the psyche or personality — in which case, the idea would seem to be that the "whole" person is one who is properly centered by virtue of having a "lord" or ruler that is not one of the competing "vessels" or special interests.

So to be "in touch with the tao," we need to be like the sage, and not like the officials. We need to be "whole" persons. We need to cultivate in ourselves that original, natural state and the "freedom from desire" which the uncarved block symbolizes.

This original, natural, "uncarved" state is not, repeat not, some sort of Platonic ideal, serene, immaterial, on a higher metaphysical plane, perfect. It is rough, not smooth — though it is also smooth. It is, in its namelessness, not the embodiment of any particular attribute in total exclusion of the opposite attribute: rough vs. smooth, round vs. not round, good vs. evil, strong vs. weak. It is an incipience, not a goal; a spontaneous thing, not a plan; an evolutionary source, not an ultimate ideal.

Because the "uncarved" state, free of "artificial desires," is not a serene Platonic Ideal, we should not make the mistake of thinking that the "desires" we are to be free of include such basic things as the need for food, shelter, warmth, health, and (I suppose) that old topic of theological controversy, sex. Only a Platonic Ideal is that unsullied. Only a Platonic Form is that single-minded. From the Taoist persepctive, it is downright unnatural not to want these things. Self-flagellators need not apply to the School of Taoism.

So if we interpret the phrase "needs fixing" as implying "deviating from a Platonic Form or Ideal," we don't "need fixing" at all. In the Taoist view, there are no Platonic Forms "out there" somewhere, to which the world to its detriment must be compared and found lacking. There are only — right here, right now — the "uncarved block" and the "artificial desires" which break it into "vessels." All that is required is the we cultivate letting the "vessels" be "ruled" once again by the "uncarved block."

Tai Chi and bladder control

I seem to be one of those guys who have a "weak" bladder. By that I mean that I tend to go from not feeling the need to use the toilet to urgently needing to go, and when that sudden urge happens, it comes upon me pretty darn fast.

I have never been likely to sleep through the night without a bathroom visit or two (or three). I have to void my bladder more often than most people do during the day, and when I do I usually don't seem to produce enough urine to justify having been in all that much of a hurry.

On rare occasion, though, I can go all night (9 hrs. plus) or an equal time during the day without a pee. When I do that, I have measured my output and found it, while not copious by "normal" standards, a lot greater in volume than my usual "gotta go, gotta go, gotta go right now" pee. I therefore know I can occasionally hold at least 9 fl. oz. or 270 ml. without any overweening urgency, while my normal "hafta run to the bathroom" output can be half that.

So I wonder: can Tai Chi help me with bladder control?

Googling on "Tai Chi" and "bladder control" online shows me that the topic of bladder control tends to revolve around (a) the elderly, (b) women of various ages, (c) people with certain conditions like multiple sclerosis, and (d) children, especially bedwetters (which I was, as a child). There's not a lot about reasonably healthy middle-aged men like me. Ah, well.

Speaking of reasonably healthy men, check out

this article, which tells of

chi gung or

qi gong master Tu Chin-sheng and what he teaches his students. The technique called

yin diao gung, or just

diao gung, literally translates as something like "genitals hanging kung fu." Through practice with heavy weights, three of Tu's male students learned to "pull a flatbed delivery truck across part of a Taipei parking lot" using just their penises!

OK, that's

not what Tai Chi is really for ... but:

Both men and women have come to Tu's chi gung classes on account of neck and back problems, joint problems, bladder control problems and other infirmities. Many of them are advanced in years, and if given the chance, nearly all of them will offer testimonial to their various cures.

... Chen Kuo-ying, age 69, came to Taiwan from Indonesia two months ago after hearing about the diao gung truck pull. "Now I have no problem carrying groceries back from the market, and I no longer have to wake up three or four times a night to go to the bathroom," he said thankfully, obviously amazed at the rapid progress he's made.

So, yes, count me as being in the market for a flatbed delivery truck!

I wrote in

Part 1 of this informal series of posts on the nature of the

tao that the

tao — the "way" of all nature, of all the "myriad creatures," and of the true Taoist sage — can be thought conceptually to

pre-exist the Western concept of God as the personification of the metaphysical One or Unity. I said:

Investigating the tao is not to deny God; it is to investigate an impersonal principle from which even our concept of God proceeds. For the tao is emphatically not a person. Instead, the tao transcends the person-nonperson distinction ... as it transcends all pairs of opposites.

Meanwhile, our conception of God dwells heavily on distinctions between pairs of opposites, such as the "war" between good and evil.

So, even though investigating the tao is not anti-God, there does seem to be an important way in which it could be called anti-theology.

Consider: We heirs of Platonic thought in the West believe, first and foremost, in the knowability of reality: that what is truly real is not consigned to be ineffable, but that it can be known definitively. True, in order for that to be the case, Plato had to posit the existence of his ideal Forms, such as the Form of Roundness, on a metaphysical level above imperfect material beings. But once he did so, it followed that imperfect material objects were inadequate, insufficient ... but by their relation to the Forms, knowable and therefore manipulable in a utilitarian sense. If men were (in the belittling word used in the Lao-tzu) "clever" enough, they could think to master the (albeit imperfect) world.

So from the axiom of knowability comes the hope of mastery: that specific outcomes can be envisioned and brought to fruition. Instead of hopefulness as a present, immediate condition, Westerners are conditioned to "hope," in the sense of looking forward to some definitive future fulfillment.

That word, definitive, is key, I think. One dictionary definition of the word is "serving to provide a final solution or to end a situation." We are reminded of the passage in the Christian New Testament's First Letter to the Corinthians: "For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known." (1 Cor 13:12).

First Letter to the Corinthians: "For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known." (1 Cor 13:12).

St. Paul is here talking about a lot of things, including faith, hope, and charity or love. But beneath it all he is talking about knowability — how inadequately we know "now," but how perfectly we will know "then." In a sense, our "final solution" as Christians is the perfection of our knowledge and our very knowability.

Again, this Jewish son of Hellenistic Greek culture, born Saul of Tarsus and later christened Paul, is heir to Plato: the reality which is the God of Jesus Christ is ultimately knowable. Therein, he says, lies our hope for the future.

And therein lies the basic attitude of Christian theology — at least, the theology to which I as a practicing Roman Catholic am exposed. We Catholics are, it is quite true, told of "mysteries" such as the three-in-one nature of the Holy Trinity, Christ's being God and man at one and the same time, the Real Presence of the Risen Lord in the Eucharist. But the attitude is: these are only mysteries due to the inadequacy of our finite human minds. If our minds were like God's mind, our understanding of these mysteries would be definitive, in another of its dictionary definitions: "authoritative and apparently exhaustive."

Again, what is real can be spoken of authoritatively and definitively — if not always by us in the here and now, then certainly by us in the hereafter, when we see God "face to face." Meanwhile, we have the theologians to teach us our doctrine, settle our theological disputes, and keep us from gross error.

The Taoist attitude is completely different. It is that reality is in the final analysis ineffable and unknowable. We can notice certain tendencies, such as that the "weak" (water is its metaphor) tends to wear down the "strong" (typified by rock). But there are no hard and fast conclusions to be drawn about what will certainly happen, and when, and why.

When you come right down to it, as Taoists we have nothing that is certain but the here and now. If we are to be happy, or joyous, or hopeful — or whatever attitude we choose to visualize, even a "bad" or "harmful" one — it will have to come right now, right this second. We must always be rooted in this Earth at this moment. For this alone is our reality ... and we through our mindfulness create our response to it, "good" or "bad."

This ongoing creation-by-mindfulness of our personal reality evolves moment by moment. It is, accordingly, organic, emergent, and evolutionary.

Contrast that approach with what we as Plato's heirs do: we wage an ongoing fight to keep our material, corporeal existence from drifting ever further away from the Platonic ideal which, putatively, is the only "real" reality. Think, in this regard, of the Catholic sacrament of reconciliation or "confession." We as Catholics are called to steadily keep track of our "sins" — the ways in which our behavior falls short of the ideal — and to recite the list periodically before God the Father and our Father Confessor with the sincere intention of reform. That "reconciles" us to God's will, which when you think about it is a personification of Plato's Form of the Good!

Cast in a more positive light, this continual attempt to "match" the actual state of the material world to some putative ideal fuels "progress": both the positive kind which benefits one and all, and the negative kind that rapes the environment and has led to such things as, for example, the Holocaust, carried out by Germans in the mid-20th century in the name of restoring the state of affairs on Earth to a quasi-Platonic ideal of so-called "Aryan racial purity."

The Taoist thinks quite skeptically of "progress." To the Taoist, progress is built on quicksand. It is the product of cleverness, not true wisdom. It assumes that hope "for" the future is more real than hopefulness "in" the here and now. Hopefulness: it's not the assumption that things will turn out right in the end. It's rather the assumption that things as they are right now are just fine, and nothing needs to be "fixed."

It's interesting how this notion of the evolving tao as having nothing to do with "progress" — with "fixing" the less-than-perfect in the world and bringing it closer to the ideal — carries over into Tai Chi. In Tai Chi, there is indeed an ideal "form," such as the Yang-style Long Form I am being taught. But it is not a form which we can ever hope to master and be done with it. Not even in concept is there a "final solution" to Tai Chi imperfection. My Tai Chi teacher Brad has been at it for 22 years, and he says the ultimately mastery of the form is just as elusive for him, in a way, as it is for me as a rank beginner. The point is to do the form, as best we can, right here, right now. The hope of future mastery is at best a story we feed our minds while we're busy doing it.

Let me again recommend the fine book

Step-by-Step Tai Chi, by Master Lam Kam Chuen.

As I have mentioned in earlier posts, what with one thing and another I've had a hard time putting individual Tai Chi moves and movements together into anything resembling the opening of the Yang-style long form. For one thing, I've had the flu.

|

Master

Lam Kam Chuen |

For another thing I'm pitifully slow at learning "kinesthetic" stuff, by which I mean (the dictionary says) "a sense mediated by end organs located in muscles, tendons, and joints and stimulated by bodily movements and tensions; also : sensory experience derived from this sense."

For yet another thing, because I know I'm bad at kinesthetic stuff, I tense up when I try it ... and that makes things even worse.

Master Lam's book is accordingly just at my level. It truly is a "step-by-step" approach to Tai Chi, and it works.

I started out less than three weeks ago doing (nearly every day) the initial set of exercises labeled "Fundamental Movements." At first, simple though they seem on paper, they were hard for me to learn and do. They were even more strenuous than I imagined they were intended to be.

They were hard to learn partly because I was being asked to formulate in my mind (true Tai Chi mavens would rather say "visualize") the movements I wanted to make, the associated breathing rhythms, etc. That was hard when the movements (not to mention the co-ordinated breathing) were unfamiliar to me. And because the movements were not in my usual repertoire, my musculature resented them, making me "feel" the exercises more than I do now.

There was a bad feedback loop going on in which one problem fed another. By the time I got done with the set of exercises, I had completely exhausted my mental ability to "visualize."

Still, they made me feel (a) good, physically and mentally, and (b) like I had accomplished something. So I kept doing them.

Furthermore, I can tell these simple exercises have strengthened and at the same time lossened up my lower back, which is a godsend in and of itself.

Meanwhile, I definitely wasn't getting at all jiggy with the form movements, so I tended to give them short shrift.

Naturally, that has led me to have an even more negative attitude toward the form.

But there's a saving grace here! The

Step-by-Step Tai Chi book ramps up, eventually, to doing a modified Tai Chi "form" which has basically the same movements I've been balking at!

After taking one through "Fundamental Movements," then "Strength and Motion" exercises, then "Balance and Movement" exercises — and, I assume optionally, "Working with a Partner" — it introduces "The Form."

The Form begins (speaking very loosely) the same way the one I've been taught begins. There's the

Tai Chi Starting movement; then

Hold the Ball (Right), which we have been calling

Hold the Chi Ball; then

Ward Off (Left),

Roll Back (Left),

Press (Left), and

Push (Left); and then the mirror-image of the above:

Hold the Ball (Left),

Ward Off (Right),

Roll Back (Right),

Press (Right), and

Push (Right).

I have faith I can work my way up to learning these moves the step-by-step way from this excellent book. It has ample, fine illustrations and clear text descriptions of what to do. If I could learn to feel comfortable with "Fundamental Movements" in just a few weeks, the sky's the limit ... as long as I'm in no particular hurry!

Oh, and there's one more saving grace. The exercises in the earlier chapters of the book are carefully chosen to "greatly aid your ability to learn a Tai Chi form at some later stage." Many of them are just moves extracted from the form. For example, the

Turning the Balloon exercise acquaints you with the final portion of the

Hold the Ball movement that occurs in the Tai Chi form. So this book is intentionally designed to offset the difficulty a klutz like yours truly has in assimilating the Tai Chi movements: it "pre-digests" them for you, so you don't have to.

The

Lao-tzu, a.k.a. the

Tao te ching — see especially the Penguin edition with introduction by D.C. Lau — presents us with a philosophy that seems elusive, even alien. Its central concept is the

tao, the "way." What is the way or the

tao (pronounced "DOW")?

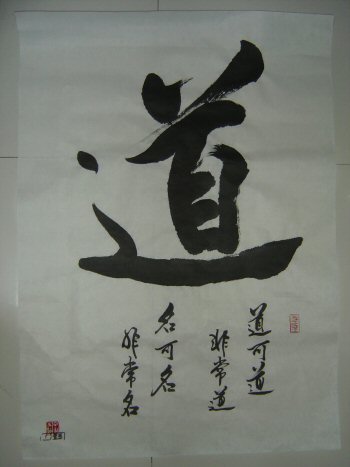

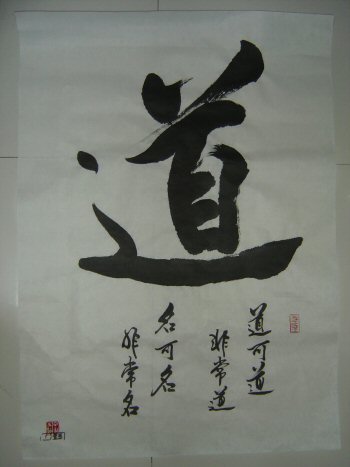

|

Tao and the

first line of

Tao te ching |

First of all, it is impossible really to speak of it, this immutable "way" of all things:

The way that can be spoken of is not the constant way (ch. 1, first line).

Accordingly, the way is called "forever nameless" (ch. 32). This "nameless" way defies all language, all attempts to pin it down in words. The way transcends thought and language.

Also, we read mysteriously in ch. 42:

The way begets one; one begets two; two begets three; three begets the myriad creatures.

Here, the "myriad creatures" are all the concrete things in the universe, animate or inanimate, with all their manifold types and categories. All owe their existence to a succession of numbers, and thereby to the tao: one (as the tao), then one (as the metaphysical One, or Unity), then two, then three (and so on).

We are reminded of the mathematicians' Fibonacci sequence: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13 ... . In this sequence, from which can be derived all sorts of geometric relationships that permeate observable nature, add any adjacent pair to get the next in the sequence. Add 0 (representing primordial nothingness) and 1 (representing the tao) to get 1 (representing the metaphysical One). Then add the first occurrence of 1 to the second occurrence of 1 to get 2, standing for the pair of opposites, yin and yang. And so on.

In this numerological way, the tao, as the first of the two 1's in the Fibonacci sequence, "is conceived of as that which is responsible for the creation as well as the support of the universe" (Lau, Introduction, p. xv).

This relationship of the tao to the Fibonacci sequence may (I humbly suggest) help overcome a confusion to which Lau himself seems to fall prey: that between the tao and "the One."

In a way, the tao can be thought of as conceptually pre-existing the One. If we think of the monotheistic God of Western religion as personifying the metaphysical One, the tao is something else — something upon which even God is based. (We read of the tao in ch. 4, "It images the forefather of God.")

Investigating the tao is not to deny God; it is to investigate an impersonal principle from which even our concept of God proceeds. For the tao is emphatically not a person. Instead, the tao transcends the person-nonperson distinction ... as it transcends all pairs of opposites.

Here we get another clue as to why the tao, when we contemplate it, seems so elusive and alien to our thought. The tao, Lau points out, "is responsible for the strong being strong [and] it is no less responsible for the weak being weak" (p. xvii). It accordingly cannot be identified with either partner in any pair of opposites (except of course as a rhetorical ploy, when so doing helps us understand it better):

Thus we can see that no term can be applied to the tao because all terms are specific, and the specific, if applied to the tao, will impose a limitation on the range of its function. And the tao that is limited in its function can no longer serve as the tao that sustains the manifold universe (p. xviii).

But, Lau shows, such talk flies in the face of our most basic assumptions in the West, inherited from Plato.

Plato vested all reality in a plurality of ideal Forms such as the Form of Roundness which, unlike all round things, uniquely is perfectly round. No material ring or orb is as perfect in its roundness. "Plato's insistence," says Lau (p. xviii), is "that of anything real we must be able to make a statement to the exclusion of its contradictory." Accordingly, we must be able to say of any truly real round thing that it is in no way, shape, or form not round. We must be able to adopt one of some pair of opposites (say, round) and wholly exclude the other (not round). Only then is something truly real.

The Taoist who reads the Lao-tzu would be mystified at this, which (per Lau, pp. xviii-xix) amounts to assuming that "the totally real must be totally knowable." That which is truly round (or truly square or truly hot or truly cold, etc.) has the advantage of being fully knowable ... even if it's only an immaterial Form or Idea, and can never be an actual object.

But the tao is just the opposite: unknowable. Or, at least, it's not totally knowable. The Taoist is "quite prepared to accept" the consequent notion that "the truth must also be ineffable."

So Plato, whose thought permeates all thought in the West, went in search of a rationale for avoiding the possiblity that "the real" may not be fully knowable, and that "the truth" may not be within our power to define.

We Westerners are, by reflex, Plato's heirs. We want, we insist, that we can take control of worldly affairs, however imperfect and "unreal," by asserting their relationship to some superior, though fully knowable, Form or Idea which alone is real and true.

It is our "can-do" philosophy which we inherit from this ancient Greek thinker. By taking reality out of the realm of the physical world and investing it in a higher order of Forms, Plato gave us the wherewithal to master the physical realm. We in the West have been doing so ever since.

Put another way, we in the West have been what the Lao-tzu calls "clever." That is, we have invested heavily in increasing our own "knowledge." In so doing, we have intensively fed our own "desire."

"Desire" is used in the Lao-tzu as a synonym for ambition, for covetousness, for ever wanting more-more-more ... for not being "content." This unbridled restlessness, Lau points out, depends on "knowledge." "It is through the knowledge of what is desirable that desire is excited," he writes (p. xxxi). "It is for this reason that," in the philosophy of the Lao-tzu, "knowledge and the clever come in for constant stricture."

And so we have a double reason why the Lao-tzu speaks of the tao in primarily negative terms. One is that the use of verbal negation — e.g., "The way that can be spoken of is not the constant way" — avoids the trap of positive statements' tendency to limit inappropriately the illimitable range of the tao's function.

And the second reason is that verbal negation is necessary to counter the Platonist lurking in all of us, especially if we are from the West. Through negation is offset our lust for knowledge — our rambunctious cleverness — and the discontent it inevitably sows. Then and only then are we open to the way, the neverending tao.

During the past several days I seem to have hit a wall.

First of all, in last Thursday's Tai Chi class I felt like I wasn't making much progress. The next day, Friday, I felt like all the zest for life about which I have been bragging was missing. By Saturday I was down with what seemed like the flu: a mass of body aches, feverishness, and so on. Was this actually a flu virus, I wondered, or was it some sort of delayed reaction to all the "strange" things I had been asking my body to do in the prior three weeks?

Meanwhile, my frustration with my inability to recall and practice the initial movements of the Yang-style long form grew and grew. I was able to do my individual Tai Chi exercises, but had no stamina or patience for anything further.

In the midst of all that I got word from my doctor that a recent chest X-ray shows there is, possibly, some sort of unexplained growth in the region of my trachea and thyroid. I'll need to get a CAT scan ... all of which (I thought to myself) is occasion for an anxiety and fear that I

don't really need right now.

Later that night, I managed to injure my shoulder while struggling with the covers in bed. So much so that the next day, Tuesday, I did no exercises.

It's is now Wednesday, and I'm starting to feel better. Without being really sure whether or not I had (still have?) a virus, without any sort of resolution concerning the abnormality on my X-ray, I feel I can at least put a foot forward again.

§

So, what happened? It is probably not consistent with a "Tai Chi mentality," I imagine, to compartmentalize my experience and assign the entire fault for my illness to an external entity called a virus. Maybe I got sick because I somehow set myself up for being sick.

Maybe I got sick because I had begun to commit a fundamental breach of

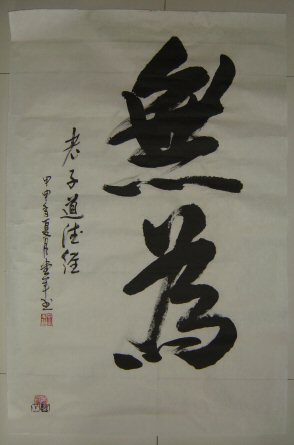

wu wei.

Wu wei is a critical notion in the Taoist philosophy set forth in the classic

Tao Te Ching (DAO DUH JING), written (it is said) by the ancient sage, Lao-tzu (LAOH DZUH). This classic is also called, simply, the

Lao-tzu, after its supposed author.

Tao Te Ching means, literally, Way-Power-Classic.

Tao equals "Way."

Te equals "Power," in the sense of the almost magical potency which the Polynesians call

mana. And

Ching equals "Classic." In English,

The Classic of the Way and its Power.

Wu wei means "taking no action," writes Sarah Allan in her introduction to one available translation of the

Lao-tzu.

This Knopf/Borzoi edition (shown at left) changes the customary order of the 81 chapters of the

Lao-tzu, so I will refer to the ordering and numbering in another edition, the Penguin Classics edition (shown at right). Both editions contain (different) translations by a single translator and expert, D.C. Lau, who also has written the introduction to the Penguin edition. The two translations are fairly close for this reason. The Knopf/Borzoi translation is based on a more-recently-found — but not necessarily more "correct" — source text than the Penguin translation.

Chapter 2 of the

Lao-tzu (in its usual chapter order) says:

Therefore the sage keeps to the deed that consists in taking no action and practices the teaching that uses no words.

Chapter 43 says:

The most submissive thing in the world can run roughshod over the hardest in the world — that which is without substance entering that which has no crevices. That is why I know the benefit of resorting to no action ...

If wu wei means "taking no action" or "resorting to no action," what does that mean?

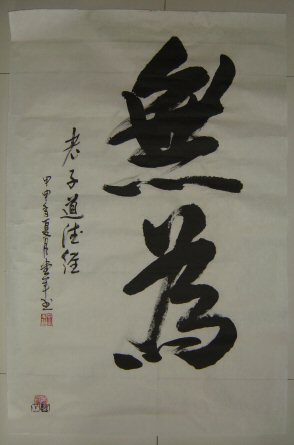

|

Wu wei

'Taking no action' |

Allan writes that "the 'action' which is to be avoided is that which is deliberate, conscious, thought out, rather than [in] spontaneous accord with the patterns of nature. Water, which takes no conscious action, but overcomes the strongest obstacle," is in effect "the most submissive thing in the world" and "that which is without substance."

In other words, we are in better accord with nature when we are more like water — submissive, without substance — than like the hardest rock, without crevices, which water nevertheless erodes away.

Allan goes on: "Wu wei is often translated as 'doing nothing', but the negative (wu) modifies the 'doing' [wei]; it is not that one does nothing, but that there is no 'action' which is not spontaneous."

§ So spontaneity is key. Per Allan: "According to [expert on Chinese philosophy] A.C. Graham, the 'Taoist relaxes the body, calms the mind, loosens the grip of categories made habitual by naming, frees the current of thought for more fluid differentiations and assimilations, and instead of pondering choices lets his problems solve themselves as inclination spontaneously finds its own direction, which is the Way.'"

Whereas at the outset of my Tai Chi pursuit I was "doing nothing," precisely in wu wei style, somewhere along the line I believe I converted it into "doing something." What I had been enjoying spontaneously step-by-step and day-by-day was now a matter of duty, haste, and greed for "improvement." I was metaphorically and literally clenching my teeth.

No wonder I got sick!

At the core of Tai Chi practice is learning a

form, which is a prescribed sequence of

movements. Each movement is apt to be made up of a sequence of individual

moves. Think of a form as an essay, a movement as a paragraph, and a move as a sentence.

A movement can also be called a

pattern, and a move can also be called a

technique. To add to the confusion, either may be called a

posture or

gate.

According to what I have been told, I am learning "the first section of

authentic Yang Tai Chi Chuan long form." Yang is the name of the Chinese

family that created this partiuclar

style of Tai Chi.

So my memory has been at fault, for I thought I was learning a Yang short form. The difference between a long form and a short form is the number of movements. In Yang long form there are up to 108 movements. Many of them are repeated here and there during the form, so a short form emerges when repeated movements are excised. But in a short form, other, non-repeated movements may be dropped also. The remaining movements my be reordered as well.

Possibly with the exception of transitional moves between movements to keep the form flowing, the movements/patterns themselves — and the moves/techniques of which they are made — don't change within any particular style of Tai Chi.

How does all this affect me? It has to do with the fact that I haven't been able to remember the first movements I have been taught, to practice them at home.

So I thought books might help. Only problem was, the first books I bought — to the extent they were Yang-style books — did Yang short form (YSF). The opening movements aren't the same as in Yang long form (YLF). Nor was it easy for me to find the YSL opening movements buried elsewhere within YSF.

That's when I became aware that my course syllabus said "the first section of authentic Yang Tai Chi Chuan long form" — not YSF!

So, back to the bookstore.

There I found

The Dao of Taijiquan: Way to Rejuvenation, by Jou (family name) Tsung Hwa, a book recommended by my instructor, Brad, that I had thought out of print.

This is a book dense with information, with little eye appeal. There are lists of movements in the forms, accompanied by profuse illustrations of each form (including Yang's Long Taijiquan starting on p. 64). But the illustrations are tiny black-and-white drawings that are fuzzy due (I imagine) to multi-generational reproduction. So they are hard to follow.

Before proceeding further, I ought to admit that I'm something of a cretin when it comes to "spatial" intelligence. Tai Chi involves complex moves in three-dimensional space, and when I see the moves rendered two-dimensionally on the printed page, my brain wants to cop out. I don't "read" these illustrations all that well in the first place.

Still, there was enough information given that I was able to recognize the third move in the Yang Long Taijiquan list as one of the initial moves I had been taught. Its name in the book, Ward-Off Right, corresponded to the name Brad had given: Ward Off. And the entire series of illustrations did look familiar.

So I forced myself to slow down and look very very hard at the diagrams, and to think about what I was looking at — certainly, one of the proverbial Tai Chi mindsets, anyway.

What I was seeing was, first of all, that (but see the end of this post) Brad is not using the same way to

get to Ward-Off Right in the form. The book lists "1. Beginning of Taiji" and "2. Ward-Off Left" as leading to "3. Ward-Off Right." Brad instead uses a different (quicker?) transition to get to the posture called "Holding the Chi Ball" which begins Ward-Off Left.

But from there it looks as if what we have been taught corresponds to what the book says. (But see the end of this post for an update.)

Specifically, the book puts Ward-Off Left in this sequence:

- 2. Ward-off Left

- 3. Ward-off Right

- 4. Roll-back

- 5. Press

- 6. Push

It then says that this list of moves comprises the movement or pattern "Grasp Swallow's Tail."

Aha! I said.

Maybe, I said — and I was whispering right out loud to myself, right there in the bookstore, my concentration being so intense; and I'm sure the other customers thought me loony — maybe we are being taught "Grasp Swallow's Tail," or some variation thereof.

So now my problem (I whispered to myself) is to find a book that describes  and illustrates the "Grasp Swallow's Tail" pattern more accessibly. That book turned out to be The Complete Book of Tai Chi Chuan, by Wong Kiew Kit.

and illustrates the "Grasp Swallow's Tail" pattern more accessibly. That book turned out to be The Complete Book of Tai Chi Chuan, by Wong Kiew Kit.

This book also has small line drawings illustrating the moves, but this time they're clear and easy to pick up on. There's also a clearly written text description of "Grasping Swallow's Tail" on page 76.

The book's main drawback is that it doesn't document Yang long form ... only a shortened, 70-movement form in the Yang style.

Still, I figure it probably can clue me in on how to do all (or most) of the YLF movements, so that by cross-referencing it with the Jou book, I can get what I need.

But there are yet more complications. For instance, Grasping Sparrow's Tail is a pattern of movement composed of several subsidiary moves or techniques. Each of the latter has a name in English and a name in Chinese.

The first is Warding Off — I'm using Wong's wording now. Jou calls it Ward-off Right (as in this case) and Ward-off Left (its mirror image). The Chinese name according to Wong is peng.

Jou uses different Chinese names for Ward-off Left and Ward-off Right. I imagine they refer to the specific move to one side or the other, while peng refers to the general shape of the move.

A difference between the Wong and Jou books is that in the latter, Grasping Swallow's Tail seems to involve both Ward-off Left and Ward-off Right, while Wong seems to think it involves either, depending on which direction you do it in.

After Warding Off in the proper direction — or in the final dierction — we do Roll-Back, the technique called (in Chinese) lu by Wong and luo by Jou.

Next comes Press or Pressing, qi or ji.

Then, it's Push or Push Out, an in both texts.

And that's all you have to do to Grasp the Swallow's Tail!

When Grasp Swallow's Tail is done to the left, it is called zuolan quewei, as I learn from this Forum post. Done to the right, it is youlan quewei. Meanwhile, Jou calls Ward-off Left zuobing and Ward-off Right youbing. So I'm guessing that zuo means "left" and you means "right," and that bing and peng are the same: "ward off."

So here, from this web page, is a Grasp Swallow's Tail Left or zuolan quewei:

2. Ward Off Left |  4. Roll Back |

5. Press |  6. Push |

Update to the above: Attending another session of the class, I learned that the opening sequence we are being taught is

just like that in the Jou Book ... with the exception that Jou's first movement, "1. Beginning of Taiji," has been replaced with "Embrace the Heavens" followed by entering a "Standing Tai Chi Meditation" posture.

In "Embrace the Heavens" we step forward with the left foot, putting no weight initially on the heel. As we do, we begin circling our arms to the sides and bringing the hands up somewhere around the height of our heads. As the hands come up and over toward the center line of the body, we shift weight forward fully onto the left foot. Then, as the circling hands start down the center line of the body, we bring our right foot forward and move it out to the right, toe down, no weight on it yet. As the hands, palms down, get to below waist level, we shift weight smoothly toward the right foot. We are in a slight crouch. Once the weight is centered, we come out of the crouch as we raise the hands to waist level, palms down, fingers relaxed. This is the "Standing Tai Chi Meditation" posture. From there we go into "2. Ward-off Left" and the rest of Grasping Swallow's Tail.

Zest for Life, Tai Chi Walking & Yin and Yang

I've been Tai Chi'ing for 12 days now, and I can report this initial finding: it has radically boosted my zest for life! Yes, already!

Call it alertness, call it a sense of well-being, call it just being fully alive — it was not my strong suit before. On my best days, life seemed something of a chore. On my worst — and there were at least a couple per week — life seemed a well-nigh-impossible burden. I called those days my "low-rez" days: "low-resolution," as in fuzzy and out-of-focus.

I haven't had a low-rez day since I started Tai Chi. What's more, I've been unusually busy, expending lots of energy. Before, one or two exhausting days would put my into low-rez mode on the following day for sure. But Tai Chi seems to have unlocked or unblocked my energy river. Now I wake up refreshed every day.

That has been so even though there were a couple of nights in a row when I got too little sleep. Possibly the river was running a bit too exuberantly. But on the day after the second semi-sleep-deprived night I definitely felt sleep-deprived ... but I didn't feel dead. (Since then I've been sleeping just fine.)

Mind you, almost all the Tai Chi I've been doing has been the set of 18 fundamental exercises in Step-by-Step Tai Chi, by Master Lam Kam Chuen. I haven't been practicing form movements because I found after last Thursday's session I had done a memory wipe on most of them, and I've as yet found no book to act as a "cheat sheet."

you, almost all the Tai Chi I've been doing has been the set of 18 fundamental exercises in Step-by-Step Tai Chi, by Master Lam Kam Chuen. I haven't been practicing form movements because I found after last Thursday's session I had done a memory wipe on most of them, and I've as yet found no book to act as a "cheat sheet."

I have been doing some Tai Chi Walking. That's an exercise in walking forward, in which you advance a foot, touch its heel to the ground without putting any weight on it, hold your balance, and then come smoothly forward, bending the knee, until your weight is fully and squarely on that foot. Then you do the whole thing again with your other foot ... and so on, and so on, and so on.

It develops the balance as it increases the strength, endurance, and proprioception of the lower extremities. And it teaches you one of the fundamental lessons of Tai Chi: visualization. In order to do Tai Chi's physical moves, first you have to visualize the successful move in your head. That visualization process helps you plan out the moves and keep them under control. It also makes sure of your mindfulness: the "realtime" connection between the body and the mind.

So I've been doing some Tai Chi Walking, and getting better at it. One trick I've picked up is to stiffen the ankle of the forward foot as it is put forth, heel-to-ground, and to point the toe firmly upward. That seems to take my mind off what I'm doing with the balance foot, letting it relax and do its thing without a lot of tipsy heebie-jeebies.

Here's a guess about that. T'ai Chi for Dummies is telling me all kinds of stuff about yin and yang. Yin and yang are the two quintessential opposites. Every pair of opposites — black and white, cold and hot, down and up. feminine and masculine, etc. — combines yin and yang.

Yin are yang  are symbolized by a circle divided symmetrically in half by a flowing line. The black half is yin, the white, yang. The complemetary small circles in each half symbolize that the seed of yin is in yang and the seed of yang is in yin.

are symbolized by a circle divided symmetrically in half by a flowing line. The black half is yin, the white, yang. The complemetary small circles in each half symbolize that the seed of yin is in yang and the seed of yang is in yin.

What does this have to do with Tai Chi? The "Dummies" book says that when it comes to using energy to move the body, soft, diffuse, "emotional" energy is yin, while hard, creative, "muscular" energy is yang. Moreover:

No movement is actually purely one or the other, yin or yang, because one part manifests yang as another part manifests yin. You are constantly shifting and moving between the two.

So I figure that when I stiffen my forward, non-weight-bearing ankle, it's manifesting yang, while my balance foot is softening and manifesting yin!

What Is Tai Chi? (Part 2)

In "

What Is Tai Chi? (Part 1)," I indicated that Tai Chi is, as an "internal" martial art, a way of exercising to stay fit and healthy

and a spiritual discipline that can bring your life into harmony.

In between the body and the spirit is the mind. Tai Chi is a martial art that turns itself into a mindful meditation.

Tai Chi encourages "moving with intent." Intent is "a mind thing," a matter of prior visualization. You cannot do Tai Chi with the body alone. You must engage your mind to do the visualizing.

Let's talk about the physical benefits of Tai Chi, but in so doing, let's keep in mind that some of the physical benefits may really come from the mind.

For example, here is a list of some of the physical benefits that, studies say, Tai Chi may offer. The list comes from T'ai Chi for Dummies:

- Better cholesterol levels

- Decreased depression

- Decreased risk of cardiovascular disease

- Increased immunity (less sickness)

- Increased muscle strength and flexibility

- Less lower back pain

- Less asthma

The problem with medical claims like these it that it's hard to test them scientifically. Why? Because of the placebo effect.

A placebo is a fake pill, or a fake treatment, that is given to test subjects when they think they're getting the real pill or treatment. Their health is apt to improve anyway. That's because their mind, convinced that the treatment is for real and that it really, really works, in some way heals the body all by itself.

The way around the placebo effect is to tell the subject that he or she may be getting a fake treatment, and that who actually gets the real treatment and who the fake is being determined at random. Not only do the subjects not know which treatments are for real, neither do the experimenters, until after the experiment has been performed.

When the "treatment" is Tai Chi, though, there's no way to administer, at random, a "fake" treatment whose distinct possibility of being fake will neutralize any preconceptions of the subject concerning the treatment. The subject knows that he or she is doing a celebrated physical exercise regimen called Tai Chi, and that it supposedly does wonders. So their presuppostions are triggered, and the placebo effect can never be ruled out.

And, accordingly, science cannot be sure whether (say) those improved cholesterol levels came from the Tai Chi itself or from the mental biases of the subject.

This is of more than academic interest. To see why, suppose there is an element of the placebo effect in Tai Chi's health benefits. Does that fact in any way devalue Tai Chi as a source of those benefits?

Not really! Tai Chi is advertised as a mind/body booster. It works on the body through the mind, and on the mind through the body. If some of its bodily benefits weren't mind-induced, that would indeed be odd!

So Tai Chi is a mind/body booster whose "mind effects" cannot be decoupled from its bodily effects for the convenience of scientists who want to study the latter alone.

Not only that, but Tai Chi, acting through the mind/body, is an elixir for the spirit. More on that in the next "What Is Tai Chi?" installment. Meanwhile, here's more on why Tai Chi is good for us physically.

T'ai Chi for Dummies says Tai Chi can have moderate benefits as a form of aerobic exercise — particularly when done vigorously. Even when done at the usual, more moderate pace, Tai Chi can lower the resting heart rate (or pulse rate) and thereby strengthen the heart, bringing down the risk of heart problems.

It also strengthens all the major muscle groups — maybe not as much as weight training, admittedly, but quite a lot nonetheless.

Further, Tai Chi beyond any doubt improves your balance, and that prevents injuries particularly in senior citizens at risk of breaking a hip in a fall. Why? It sharpens your proprioception: the "body awarness" of your muscles and their nerve endings (see the earlier post, "It's Not Just Me: Proprioception and Tai Chi").

That improves balance, and so does the strengthening of the abdominal and leg muscles so crucial to being able to balance on one leg.

Tai Chi not only helps avoid injuries from just living life or from other forms of physical activity, it also helps rehabilitate injuries you do sustain.

On top of all the above, Tai Chi measurably reduces stress and anxiety, lowers depression, confusion, and tension. It improves mood, and it gives us a sense of well-being.

Tai Chi can help control high cholesterol and high blood pressure, combat asthma and breathing woes, and relieve arthritis and other chronic pain.

Finally, not only does Tai Chi improve muscle strength, it also increases both muscles' endurance and their flexibility.

Not bad at all for a "medicine" that's basically free and is fun to "take"!

It's Not Just Me: Proprioception and Tai Chi

Earlier, in

this post giving my first impressions of Tai Chi, I spoke of two particular challenges I'm experiencing as a Tai Chi newbie: poor physical ability to keep my balance, and poor "body awareness." The latter I illustrated as a failure to be aware of my actual posture with respect to keeping my shoulders right over my hips, thereby provoking lower-back discomfort.

It turns out that the two issues, balance and body awareness, are more closely related than I knew, or so a book I have bought tells me.

I went to the bookstore the other day and got four books that illustrate Yang-style Tai Chi notably well, one of which is (I'm almost ashamed to admit),

T'ai Chi for Dummies.

Early on, it talks about how Tai Chi improves folks' ability to balance. It mentions the problem of "weak ankles or weak lower legs," and I thought, "That's me all over!"

Tai Chi fixes that. Says the book, "The improvements happen because of training better proprioception of the nerves and muscles of the lower legs. Loosely translated,

proprioception is sort of like tickling the nerves and muscles to improve the muscle sense of the body's position in space." That, in turn, improves the balance. "With better balance, you don't wobble as much or turn your ankles as often."

So balance depends on proprioception. And propriocepetion, kinesthetic awareness, and body awareness are very close to one another in concept, says "Training for Proprioception & Function," an online article

here. They all have to do with "understanding how the body communicates with itself."

So when I complain of back discomfort and labored breathing associated with not keeping my shoulders, hips, and knees in proper relation, thereby arcing my back and over-tensing my diaphragm, I'm talking about a paucity of proprioception on my part, a lack of kinesthetic awareness, a deficit in terms of how my body communicates with itself.

For all of which, Tai Chi is my chosen antidote!

What's more, it's therapeutic just to read in this book that poor proprioception is a common malady. It's not just me! What a relief to know that!

On Posture, Breathing, and the Diaphragm

As I mentioned in an earlier post, Tai Chi is designed to (among all sorts of other things) correct our breathing.

I also mentioned that Brad, our weekly class instructor, says the right bodily posture is such that the shoulders are positioned right above the hips — thus relieving back strain.

Guess what I just discovered, by looking at myself in a full-length mirror while standing sideways to it? When I adopt a "correct" posture with my shoulders right over my hips, if I also bend my knees

just slightly, I find that my diaphragm automatically "loosens up" and my breathing becomes a lot easier.

Not only that, but it also becomes quite easy for me to get a comfortable and correct-looking posture in terms of how my chest and throat area open up. My shoulder blades can be consciously pulled just slightly together (compared with how I normally carry them). That pushes my chest out a tad.

What's more, my head and neck are well-positioned and under less strain than usual. That effect comes from the fact that slightly bending my knees tilts the bottom of my spinal column forward and the top of my spinal column back an inch or two from where they would otherwise be.

By way of contrast, my normal — albeit incorrect — posture has me arcing — or arching, or tensing; whatever you want to call it — everything from the bump at the back of my skull down to my "tailbone." It's as if my "inner mother" is telling me to "stand up straight" all the time, and I interpret that as meaning I need to arc my back.

So it's easier to "hold my head up" when I stop "standing up straight" and make all the corrections I just described. Or, put more aptly, it's a different, and better, way of "standing up straight," as the mirror confirms.

Ergo, posture is a whole-body affair, and when it's right (a) there's much less strain, tension, fatigue, and so on and so forth in

various parts of the body and (b) the diaphragm is relaxed enough to let the breathing be free and easy in both directions, in and out.

Point (b) about the diaphragm is a biggie, in my book. For years and years I have apparently been carrying about with me an awful lot of excess muscular tension. It expresses itself, as I say, as a tendency to arc my back with my legs ruler-straight, my knees locked, and my "tailbone" pointed too high. That "feels like" the proper way to stand. Even though I now see it's way off the mark, I always correct to it, automatically and without thinking.